Running on Borrowed Time

A Cautionary Tale

Ted Guloien

A fully committed runner will follow treatment for any problem provided it does not have as its goal cessation of running.

Dr. Lowell D. Lutter, 1984

With hindsight, he knew the genesis of what happened likely began much earlier, perhaps in his childhood and certainly by the time he reached end of his twenties. But his childhood was long over, and that wild decade of excess had ended 30 years prior. Much had changed. He had stumbled into running in his mid-thirties, embraced a healthier diet, dropped junk food, and stopped smoking. Having children will do that to a person. His BMI was 23.3, his body fat percentage 12.2% and his resting heart rate 48 beats-per-minute. And then it wasn’t or, rather, he wasn’t.

When he perceived it started was in May 2013, less than two weeks after his 60th birthday. He was alone on his regular 10k lunchtime run, heading northeast from the YMCA. Somewhere in the first 3 kilometres pain etched across his shoulders. He stopped for a drink of water at a park fountain, noted the pain as an exception and finished the run, averaging a pace of 4:43 minutes per kilometre. It was an otherwise unremarkable run but for the light rain.

Running Diary for May 22, 2013: “The first leg to the fountain was difficult. Pain in shoulders. But rest of run was excellent. Little rain. Weight = 165 lbs.”

By that age, he’d had very few substantive running injuries, the most notable resulting in partial meniscectomies in both knees, a year apart, back when he was only 53 years old. His surgeon advised against continuing to run. He didn’t perceive that as an option, so the surgeon with his Irish accent advised that he run in a “spritely” fashion. Two years later, he ran his 5th Boston Marathon. To him and his running buddies, pain was just a part of running: you either ignored it or allowed it to slow you down. They also told each other: “You’re only as good as your last race” and “Your time is your time”. Runners’ stoicism. As for the shoulder pain, he kept his weekday and Sunday long run schedule for the rest of the month and into June.

Early in June the pain returned. He was running the usual 10k lunchtime route with two others at a 4:41 pace. But this time the pain got his attention.

Running Diary for June 11, 2013: “Chest pain again during 1st 3 km, before fountain, at HR of 153. Pain above the sternum on both sides, radiating into shoulder joints. Not crushing pain but permeating pain. After water at the fountain, ran faster to increase HR to 163+ but no pain whatsoever. After the second fountain break, took off heart monitor to see if it was constricting chest. No pain but heartburn. Weight = 162.8 lbs.”

The following day, the same pain re-occurred, but earlier in the run, while at a slower pace. He was alone. Like the day before, the pain disappeared after the first water break and did not return over the course of the run. He made an appointment with his GP for the next day.

Doctor Fred, his physician since he was a young man in graduate school, was as surprised and concerned as he was. Fred knew his medical and running history and, while he thought a cardiac issue was unlikely, scheduled a treadmill stress test and echocardiogram for the end of the month. “You do a stress test every time you run”, Fred told him once before, when he reported chest pain. This time, the pain described sounded like angina, a sign of coronary artery disease and a symptom of the heart not getting enough blood. The day after visiting Fred, he was back outside on the 10k route doing intervals. His average heart rate was 149 beats per minute and the maximum was 170.

Running Diary for June 14, 2013: “Did fartleks/intervals of 2 X 1km across the Glen Road Bridge. Chest pain started later today, wasn’t as severe but it came back a little during the final push to finish. Weight = 162.2 lbs.”

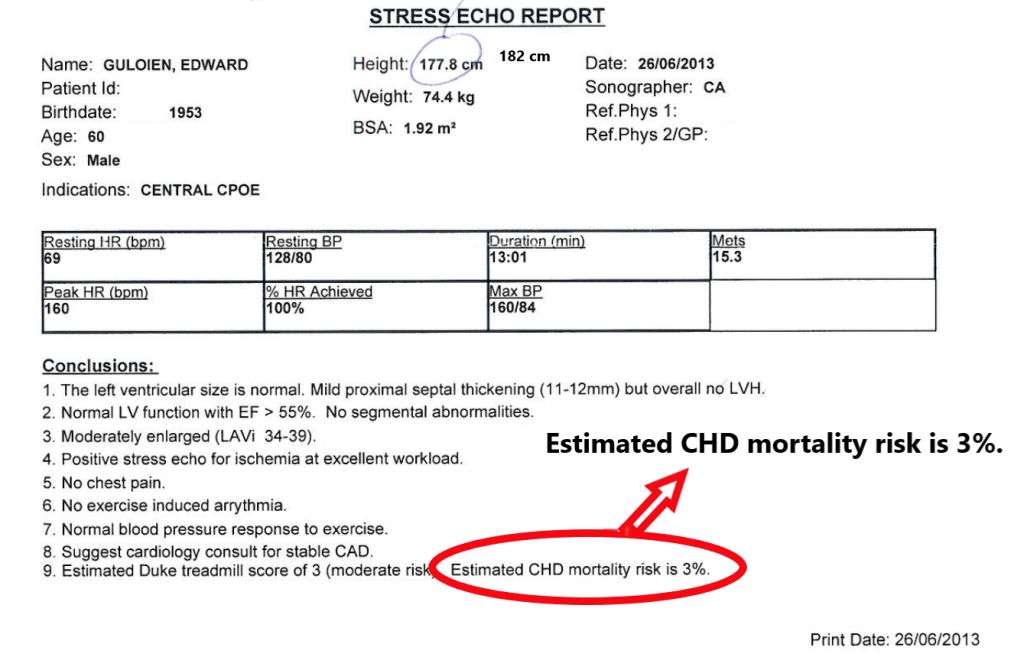

On June 26 he was at the hospital cardiac clinic dressed in his running clothes, ready for the treadmill. He immediately felt more comfortable in his familiar gear, in spite of the sterile cold environment and his anxiety about why he was there. While this was his first stress test, he was very used to treadmills. He hoped the diagnosis was going be gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD and had scoured the medical sites on the internet, hoping for any diagnosis but a cardiac issue. As the stress test loomed, he recognized it would be the arbiter, not Google.

The attending cardiologist, Dr. X introduced himself with “So, here’s the great Mr. Guloien” in front of the cardiac technicians and nurses. When Dr. Fred referred him for the testing, he included on the form that his patient was a marathon runner and cyclist in excellent shape. The introduction was as embarrassing as it was puzzling. The treadmill experience was different from what he was used to at the YMCA: the speed increased in a stepwise fashion, as did the slope of the treadmill surface, and he was attached to ECG leads on his chest. The hardest part of the test was jumping off the treadmill at its termination and immediately lying down for the echocardiogram. The echo technician wanted his heart pumping at near maximum exertion, so he had to make the transition quickly.

The treadmill test was stopped when the target heart rate of 160 beats per minute (bpm) was achieved. He felt no chest pain or other discomfort and achieved 15.3 METS, a measure of exercise capacity. An exercise capacity of 13 METS or more indicates a good prognosis, even when there is an ST depression on the ECG, as there was on his. He had cardiac ischemia – not enough oxygen-rich blood was getting to his heart muscle at peak exertion – a strong indicator of coronary artery disease. The echocardiogram confirmed it: his left ventricle, which pumps blood to the rest of the body, dilated at peak exercise (LVEF = 65%). Yet, given his good level of exercise capacity, it was estimated that his coronary mortality risk was 3%. The diagnosis of coronary artery disease was a gut punch. He had mistakenly assumed that because he was athletic, he was healthy.

He asked Dr. X if he could keep running. The cardiologist said the benefits of running outweighed any potential risks but to try to keep his heart rate below 120, as a precaution, for the time being. After the stress test, he walked to the YMCA for his lunchtime 10k run with two other runners, running at a fairly casual pace of 5:13/km. Even at this relatively slow pace, his maximum heart rate was 171 bpm.

Running Diary for June 26, 2013: “After the echocardiogram exercise stress test, went for a run. Got 2 km into the run and stopped due to chest pains. (Woke in the middle of the night before with acute chest pain, from indigestion?). HR seemed elevated, especially for the relatively slow pace (i.e., 150 HR at 5+ minute pace). Slow run back.”

Until his July 10 follow-up appointment with Dr. X, he decided to back off intense running in favour of walking, cycling and more casual running. He started walking home from the office, a distance of about 7 km. He also tried to warm up before running, to give his blood vessels time to dilate (expand) to accommodate his heart’s need for more oxygenated blood. Over this four-week period, he had no chest pain. His research and plan seemed to be paying off.

Running Diary for June 29, 2013: “Post echocardiogram stress test, cycled to Joe’s but tried to keep HR under 120 bps, as per cardiologist’s orders. No angina pain.”

Dr. X prescribed nitroglycerin tablets for the angina (the chest pain associated with ischemia) and told him to put one under his tongue when the pain presented. He was to take aspirin daily, to prevent blood clotting, and was also prescribed atorvastatin to reduce his “bad” cholesterol and protect the plaque in the cardiac arteries from rupturing. While his cholesterol levels were excellent, Dr. Fred told them they had to be lowered, given the diagnosis of coronary artery disease. He tried arguing with Dr. Fred that he could switch to a plant-based diet to reduce his cholesterol. Dr. Fred wasn’t buying it, saying only 20% of cholesterol came from the food he ate and noted that statistics for maintaining a plant-based diet were not encouraging. Dr. Fred said he would be on statins for the rest of his life.

Running Diary for July 31, 2013: “Best run in a long time. Lots of energy and no chest pain. Ran fast at beginning and built up to 4:30 pace. Weight = 160.4 lbs.”

He had prepared questions for the cardiologist about what comes next to fix the issue. As for his future, Dr. X said, collateral blood vessels would bypass the coronary artery blockage and restore good circulation to the heart muscle. Until then, he said, keep up the running but keep the heart rate below 120 bpm. After running 26 marathons in adulthood and countless shorter distances, and enjoying it all, he wasn’t prepared for this outcome. His only hope was the collateral blood vessels.

Running Diary for August 9, 2013: “Ran a warm up 1 km before running, to warm up coronary arteries. Not effective; still had chest pain at and beyond the 1 km mark. But gone after Craigleith Gardens, and when I did the 1 km fartlek across the Glen Road Bridge. No chest pain thereafter. Weight = 159.6 lbs.”

He never used the nitroglycerin tablets. Nitroglycerin is a vasodilator and one of the side effects was headaches. He was never prone to headaches and saw no reason to start now. Besides, angina was a symptom and not a life-threatening disorder. As long as he stopped his activity when the pain presented, and let it pass, his heart wouldn’t be damaged from the angina. The pain was manageable. It would appear early in the activity and vanish, after a short break, leaving him free to continue.

Running Diary for August 28, 2013: “Sunny, hot and humid. Chest pains on Earl Place, about 1 km into the run. Slowed down to miserable pace and pain subsided. After fountain, did 4:30/km interval with no pain. Onset of pain at 6 km mark but stopped before and at fountain. No pain thereafter, in spite of higher HR and faster pace. Weight = 157.6 lbs.”

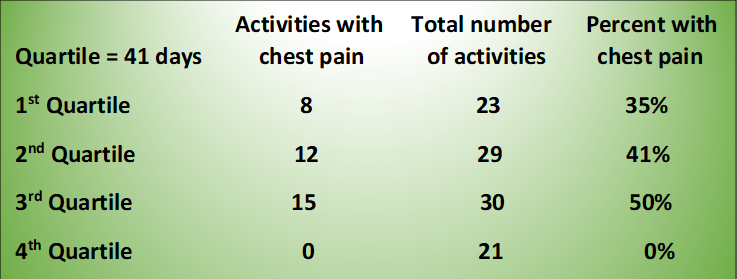

Between the first experience of chest pain that May and the half-marathon he entered in early November, he ran or cycled a total of 103 times. During a third of these exercise activities, he experienced chest pain.

However, in the final quartile of that May-November time period, the chest pains disappeared completely, even though the intensity of the exercise remained the same. His conclusion: collateral blood vessels.

During that last quartile or 41-day period, he cycled his first Gran Fondo, a distance of 140 km, at an average speed of 30 kph. His average heart rate was 146 bpm and the maximum was 165. No chest pain. He went to France and, on a whim, rented a bicycle, changed into his cycling clothes in a farmer’s field, and cycled up Mont Ventoux, part of the Tour de France. His average heart rate was 140 bpm and the maximum was 168. On the way down the mountain, his tire flatted out. Because of the altitude, there was no cell phone reception, so he couldn’t tell his wife he’d been delayed. He changed the tube and continued down the mountain. No chest pain. In October, he and his three partners closed down their practice after working together for 30 years. No shortage of heartache but no chest pain. He felt he was back to being normal. Life was good.

On October 30, he met again with Dr. X, the cardiologist. He wanted feedback on his running a half-marathon four days later, on November 3. During this visit, he was prescribed an ace-inhibitor, as the cardiologist felt his blood pressure was too high. It had never been high before. Dr. X okayed running the half-marathon, as long as he took it easy.

He hadn’t been training specifically for the distance, so taking it easy was his plan. He had run a half-marathon with his daughter in March and beat her handily at 1:44 (average HR 149 and Max HR 173) and at an 8k hilly race in April, where he placed 3rd in his age group. He was prepared to smile as he crossed the finish line as she waited there for him this time, having beaten him. It didn’t work out that way.

It was a crisp sunny autumn morning at the start line, in a city 75 kilometres from home. He could see his and the other runners’ breath. He was wearing his blue 2010 Boston Marathon long-sleeved shirt. It was his favourite. His daughter beside him and his wife waving from the side of the road, the air horn sounded the start. He and his daughter ran on the side of the road to avoid the slower runners in the middle. Slowly she pulled away and he watched her pink jacket bob in and out of the runners ahead. As the course turned north, the escarpment allowed a sweeping view of the snaking trail of runners heading for the lake. He soon joined them and was running toward the finish line with the lake and the sun blinking through the trees to his left. And that’s where his memory ended. Others would have to fill in the blanks.

But then a trim, fit looking runner with a Boston Marathon shirt kind of fell in front of me. He kind of stumbled and collapsed… only about 200m from the finish line. I ran over to see if he was hurt. He was lying face down, still breathing, but not answering me when I asked him if he was okay or what his name was. Then he appeared to stop breathing. So a woman joined me and we rolled him over and checked for a pulse. He didn’t have one. So I yelled for someone to get an ambulance. And we started CPR.

Rob (a spectator watching for his wife in the race)

We turned around to see a half marathon runner collapse just 20 feet away. My sister-in-law Brenda, who is a nurse practitioner and also 7 months pregnant, sprinted towards him. The runner did not have any vital signs. Brenda and another man began chest compressions immediately.

Maria (among her family, watching for her father and brother in the race)

I spot a runner face down on the pavement. He isn’t moving. I run towards him, but another spectator gets there first and yells for medical help. The downed runner is smack in the middle of the narrow race course and runners are now pouring directly towards the emergency scene. We start diverting them around the obstruction and recruit several more volunteers to the task. The approaching runners are confused. They think we’re high-fiving them as we motion with our arms.

Art (had finished the race and was walking the course, looking for his friends)

I am with a man in blue and I’m sticking with him. I run and run as hard as I can. Race to the finish. I can hear the finish and taste the victory. All of a sudden there is a man down in front of me with people all around him. I see them roll him on his back and someone assumes a CPR position. As I run past I think, “I should stop.” And think, “They’ve got it under control.

Nicole (running the race)

There was a runner just standing in the middle of the path. Dude! I thought to myself until I realized he was telling us all to move over, that behind him there was a crowd. A crowd surrounding a man. A crowd surrounding a man who was receiving CPR. A man who was receiving CPR whose eyes I looked right into and saw nothing there. “Oh my God” I whispered. Or yelled. I can’t quite remember. I just remember being so horrified. So I ran.

Sam (running the race)

The St. John’s volunteers are working furiously. I have never seen CPR in action, and the brutality of it is shocking. The woman crouched over him crushes his chest with each compression. The runner is motionless, his body absorbing each thrust like a foam pillow. If you didn’t know what was going on, you might suspect a gang was beating up an unconscious man on the ground, the procedure is so violent.

Now there are five or six people clustered around the runner. They strip his shirt off. Someone arrives with a defibrillator. We hear a tense voice barking orders as they apply the electrodes and jolt his torso with electricity. More rapid CPR.

Art (had finished the race and was walking the course, looking for his friends)

After 10 minutes, an ambulance pulls up and two paramedics jump out. The paramedics join in on the CPR. but I still see no response from the runner. Our runner is loaded onto the stretcher and then wheeled back to the ambulance. I watch as he goes by. He’s motionless. No colour in his face, his head slumped to the side. He doesn’t appear to be breathing. I assume he’s dead and they’ve all but given up as they load him into the vehicle.

Art (had finished the race and was walking the course, looking for his friends)

An automated external defibrillator had been brought to the scene by the Marathon Event Medical volunteers but was unsuccessful in converting heart rhythm. Hamilton EMS was successful with the use of their AED and associated medications.

Jeff (St. John’s Ambulance)

Marathon Runner Collapses Near Finish Line. A runner is in serious condition after collapsing near the finish line of the Hamilton Road2Hope Marathon. After 10 a.m. on Sunday, paramedics rushed to Confederation Park after receiving a call about a fallen runner whose vital signs were reportedly absent.

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation CBC News

It was described in the hospital medical records as “witnessed ventricular fibrillation”. Instead of rhythmically pumping blood to the rest of the body, his heart was quivering like a block of cherry Jello flicked by a child. With no oxygenated blood being pumped from the heart to sustain it, his brain shut down in a sequence, like lights in a stadium. He was unconscious before he hit the path on which he was running. As his brain function stopped, so did his breathing. No pulse. No respiration. Vital signs absent. Cardiac arrest.

But for the quick response from bystanders and medical personnel, and a stubborn Emergency Room nurse who organized them all and refused to stop the CPR, he would have died on the running path. From falling on the path to the ambulance departing with him for the hospital, 22 minutes had passed. His daughter and wife heard the ambulance siren as they looked for him in the crowd of exuberant runners. A policeman drove them to the hospital where his wife was told to prepare herself as he might not survive.

His wife’s texts to the family:

- Nov. 4: Ted continues to sleep as scheduled. Early tomorrow morning they will reduce the medication so he can wake up. Apparently people vary widely in terms of how long this takes, so some time tomorrow is the best estimate we have. After he wakes up they can better assess his situation. So we are waiting patiently.

- Nov. 5: Ted has opened his eyes and wiggled his toes! This is great news! It may be a while before he does anything else.

- Nov. 5 at 10:39am: Ted is awake and fully coherent. He knows who we are and is talking.

- Nov. 5: Ted sitting up making jokes and asking for coffee.

- Nov. 5: Ted doing great, all tubes out and he had lunch.

Two days later, in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit at Hamilton General Hospital he was brought out of the induced coma and hypothermia, and that evening received a finisher’s medal from the race organizer. With tears in his eyes, he accepted the gift, recognizing it was his first DNF.

The angiogram performed in the hospital indicated his left anterior descending cardiac artery was over 90% blocked. Ventricular fibrillation, likely triggered by exercise demand ischemia. In stark contrast to the predicted 3% probability of a major cardiac event, a sudden cardiac arrest turned out to be a certainty, just waiting for the right moment. Had it occurred weeks earlier, isolated on Mont Ventoux in France, the outcome would have been different.

His heart recovered much faster than he did. His self-confidence crumbled. He felt his heart had let him down and was ashamed by how and where it chose to do so. In time, he came to realize that he had let his heart down. His runners’ denial and stoicism nearly cost him his life. At the same time, his stubborn pursuit of running helped mitigate the seriousness of the consequences. His heart was not damaged. He would run again.