It was a sunny warm day in August 2019, and we were on our front porch finishing lunch when a tall lanky man strode up our path. With his subtle Norwegian accent, he explained he had read about our recent visit to my great grandfather’s former farm in Alvdal in a digital Norwegian newspaper. He was helping out a friend on our street with her gardening, and he thought he’d introduce himself. He stayed for a cup of tea. This was my introduction to Tore Maagaard.

Tore and I began to meet downtown for coffee. He lived near Yonge and Davenport, so we’d meet nearby at Balzac’s Coffee inside the Toronto Reference Library. Tore was from Stange, in Norway, which is south-west of Alvdal and where my great grandfather and family lived for a couple of years before emigrating to Canada. While from Stange, Tore liked Alvdal, so much so that he purchased property there back in the 1970s with the intention of building a home. Tore encouraged the exploration of my Norwegian heritage, bringing me information and a bygdebok from Stange that detailed local family histories. While our relationship was initially based on our connections to Alvdal, over our subsequent coffee dates we talked less about Norway and more about our lives. I enjoyed listening to Tore’s stories.

Russefeiring in Alvdal, 1962. Tore (circled in red) drove the tractor that pulled the old Alvdal fire truck.

Tore left Norway when a lot of young Norwegians left to explore the world, before settling down, in the late sixties and early seventies. He came to Toronto and landed a job teaching Torontonians to ski at the North York Ski Centre (at Earl Bales park). He lived in a house on Dundonald Street, in the Yonge-Wellesley area, with a collection of other young Scandinavians. Coincidentally, in the 1980s, I worked in an office only a couple of doors east of where he lived. The house in which Tore lived was owned by Frank Hansen, a Danish restauranteur who owned the Vikings Dining Room and the Stable Bar, both on St Nicholas Street on the west side of Yonge and a block north of Dundonald. The young men would pile into Frank’s car and, consulting the bargain restaurant deals in the newspaper, drive around the city looking for cheap eats. It took some time for Tore and his companions to realize they were living in Toronto’s gay village. And when they did, only after one of them was propositioned, it mattered little to them.

Tore eventually became the manager of the Ski Centre and hired friends from Norway, including some from Alvdal. Invited to a formal City of Toronto Christmas dinner with the head of Parks and Recreation, Tore decided to bring along a new recruit from Alvdal as his “plus-one”. Not totally familiar with the language customs of his new environment, the young man was sharing a ski instruction story with the table and employed a term to describe one of his adult ski students that he’d only recently heard yelled in the neighbourhood: “That cocksucker went flying down the hill.” The awkward silence was broken only when Tore explained it was an error in translation.

Tore’s landlord, Frank, a proud Dane like his contemporaries at the Copenhagen Room and Danish Cheese Centre on Bloor Street, was heavily involved in Toronto’s Caravan: the annual festival celebrating the city’s multiculturalism. This was in 1968, before Canada officially announced it was embracing multiculturalism as a policy. For a small $2 fee, one could purchase a passport to visit the various cultural pavilions spread across the city in church basements, store fronts and tents. Chartered buses would shuttle people between the pavilions so they could enjoy the country’s food and beverages, arts and crafts, and performances. Frank enrolled his young Scandinavian charges to work in the Danish pavilion. The young Scandic helpers drank more of the Danish beer than did the paying customers.

When winter ended in Toronto, Tore and his companions would travel around North America looking for adventure. Tore was especially fond of the west coast. At some point in the late 1960s, Tore attended Ryerson Polytechnic and graduated with an undergraduate degree in community service (a precursor to social work). Tore left Canada in the late 1970s for Scranton, Ohio, where he graduated with a Master of Social Work degree from Marywood University. For his thesis, Tore lived in New York City and interviewed and then surveyed immigrant Norwegians to understand the role and gaps in service of the Norwegian Seaman’s Church in helping them adapt and settle. The church used his research to align their work with the expressed needs.

Tore worked at the International Institute of Metropolitan Toronto, which provided support services for new immigrants. As an immigrant himself, Tore became one of a new breed of social workers who, in the spirit of the Caravan festival, were trying to build bridges between Toronto’s immigrant communities while helping them adapt to their new home. Tore worked at Whitby Psychiatric Hospital (now Ontario Shores Centre for Mental Health Sciences), and other GTA hospital, and ended his career at St. Joseph’s Health Centre in West Toronto. But even after retirement, ever the social worker, Tore kept practicing his craft as he helped manage the affairs of friends and acquaintances who had little or no family support. When I tried to schedule a coffee visit with Tore, he would consult his calendar and invariably be busy meeting lawyers, doctors, and social service workers on behalf of those he was helping. He was a very busy and compassionate man. Helping others gave Tore a sense of purpose.

Tore had planned a trip to Norway earlier in the year and we had not yet discussed how it went and who he had visited. He had a brother and nieces and nephews in Stange and friends in Alvdal, and we had talked about meeting in Alvdal sometime in the future. Like many wanderlust Norwegians, Tore enjoyed travelling, especially on cruises with his wife Liivi. Tore knew we were investigating the purchase of an EV and was anxious to hear our decision as he wanted to buy whatever vehicle we chose. “Maybe we can get a discount if we buy them at the same time” he suggested with a small smile.

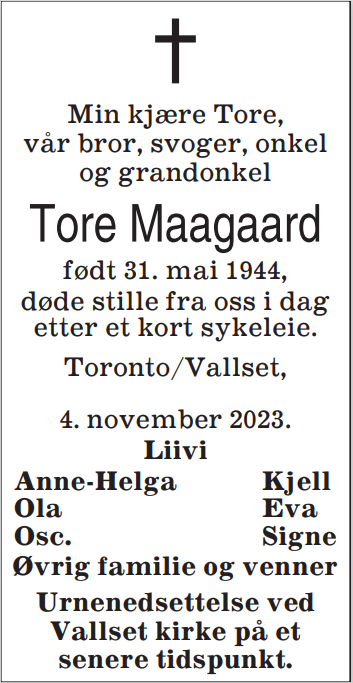

I realized at Christmas that I hadn’t heard from Tore in a while. When he didn’t respond to my outreach, I went online and discovered a “dødsannonse” or death announcement in the Oslo Aftenposten and Hamar Arbeiterblad newspapers. Liivi contacted me. At the end of October, Tore fell and had a brain haemorrhage. He died on 4 November. A service will be conducted at the Vallset Church in Stange, Norway at a future date.

Tore Maagaard was a born social worker and his avocation influenced much of everything he did. And underneath his taciturn personality was a very playful man. I will miss his wry sense of humour. I will very much miss him.

Tore placed a sibling group of five with my husband and me in 1973. He was a wonderful friend besides a dedicated social worker who attended our 30th anniversary of the adoption. We wanted him to be here i May for our family reunion and 51st adoption anniversary. We all loved him. He will be greatly missed.

I sometimes forget and think I should phone him to get together. Thank you for sharing your memories.

Friend of Tore from St. Joe’s Hospital.

Enjoyed your obit. Meeting with his nephew today in Toronto. He would like to connect with you. Please contact me at the contacts below…

Hei sory to see that Tore have past away.

Tore was a god frend of my familien when he live i Alvdal , he olso visit me in Molde when he visit his brother live close to Molde Averøy, thinking om him.

Best reg

Erik Holm

Tore fortalte meg mange historier om vennene sine i Alvdal. Han elsket den lille landsbyen.

Ted

I knew Tore in the late 1970’s when he was running the cross country skiing at Earl Bales and I was managing the Uplands Ski Centre. He was a great friend and a bit of a mentor He also arranged for me to hire a Norwegian to run our cross country operations for numerous years.

Bruce

I didn’t know Tore that well but enjoyed his company and was looking forward to knowing him better. I even thought we might meet some day in Norway. I’m still surprised I haven’t heard from him. And then I remember.

Ted

Reading this piece felt like walking through a beautiful garden of ideas — each thought more inviting than the last.